‘Really angry’: Why Canadians with long COVID struggle to access financial aid

Robert Morley is not a long-COVID sufferer, but his experience is in many ways a preview of what people who have developed severe, long-lasting symptoms after COVID-19 infections can expect as they adjust to life with a poorly understood disability.

He can only read a few pages of a book at a time if he wants to avoid extreme fatigue and headaches. Moving between the bed and the couch in his Ottawa home is all the walking he can muster in a day. And the 52-year-old, who was diagnosed in 2010 with myalgic encephalomyelitis, commonly known as chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), hasn’t been able to work for nearly 15 years. Instead, he has had to spend much of the very little energy the illness leaves him fighting to obtain financial assistance for his disability.

The uphill battle patients with ME/CFS often face in accessing both insurance and government disability benefits is why advocates worry about the financial future of Canadians with long COVID, whose numbers are swelling as the pandemic stretches into its third year.

It’s not just that long COVID and ME/CFS share a multitude of symptoms, including brain fog, debilitating fatigue, memory and speech issues, muscle pain and weakness. Both conditions are also invisible and hard to diagnose, traits that notoriously complicate both insurance and government disability benefit claims, experts warn.

Long COVID is the term commonly used to describe what doctors call “post-COVID condition,” a plethora of symptoms that affect some people long after an initial coronavirus infection, sometimes making it hard for them to function in everyday life.

While Canada doesn’t yet have an official tally of so-called COVID long-haulers, between 10 per cent and 20 per cent of those who have contracted COVID-19 experience symptoms that last for at least two months, according to the World Health Organization – though those symptoms vary in severity. Based on those estimates, Canada’s 3.9 million COVID-19 case count to date puts the number of long-haulers in the hundreds of thousands.

Some who caught the virus early on in the pandemic have been unable to work for more than two years now. Others went back to their jobs but are routinely having to use vacation days or unpaid sick leave when their symptoms become unmanageable, according to Jonah McGarva, a Burnaby, B.C.-based long-COVID survivor and advocate.

Some could manage to work part-time or remotely. Instead, financial necessity has forced them to resume full-time jobs – sometimes in-person – that make them sicker, Mr. McGarva said.

He recalled a conversation with a fellow long-hauler who described curling up in a fetal position in her home’s entrance hall as soon as she made her way through her front door after a day of work, because she was so exhausted.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/XXBAKPDREVCAPIDNOVCFJUUMCQ.JPG)

A Siemens Magnetom &t MRI Plus unit at Western University’s Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping.GEOFF ROBINS/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Sonya Torreiter, a speech-language pathologist at Providence Healthcare’s Post-COVID Condition Outpatient Clinic in Toronto, described a long-COVID patient in a similar situation. The woman, a financial services professional, told Ms. Torreiter she often had to lie down on a couch between work meetings. At the end of each day, Ms. Torreiter said, the patient would crawl up the stairs and go to bed, unable to make dinner or spend time with her kids.

And some long-haulers who can’t keep up with the demands of their old jobs are being laid off, Mr. McGarva said.

But as more Canadians with long COVID try to apply for insurance and government disability support, many are encountering the same hurdles that have long been familiar to Canadians with ME/CFS.

Mr. Morley, for one, never had a chance to apply for his workplace disability group policy. It took years for doctors to link his symptoms with ME/CFS, which remains a poorly understood condition. By the time he received a formal diagnosis, he had already lost his job, after years during which his workplace performance had been deteriorating in tandem with his health, he said.

Even with a diagnosis in hand, it took several more years for Mr. Morley to definitively establish his eligibility for the disability tax credit (DTC), a federal non-refundable tax break for people with disabilities. He was denied the credit repeatedly.

Limited access to the disability tax credit

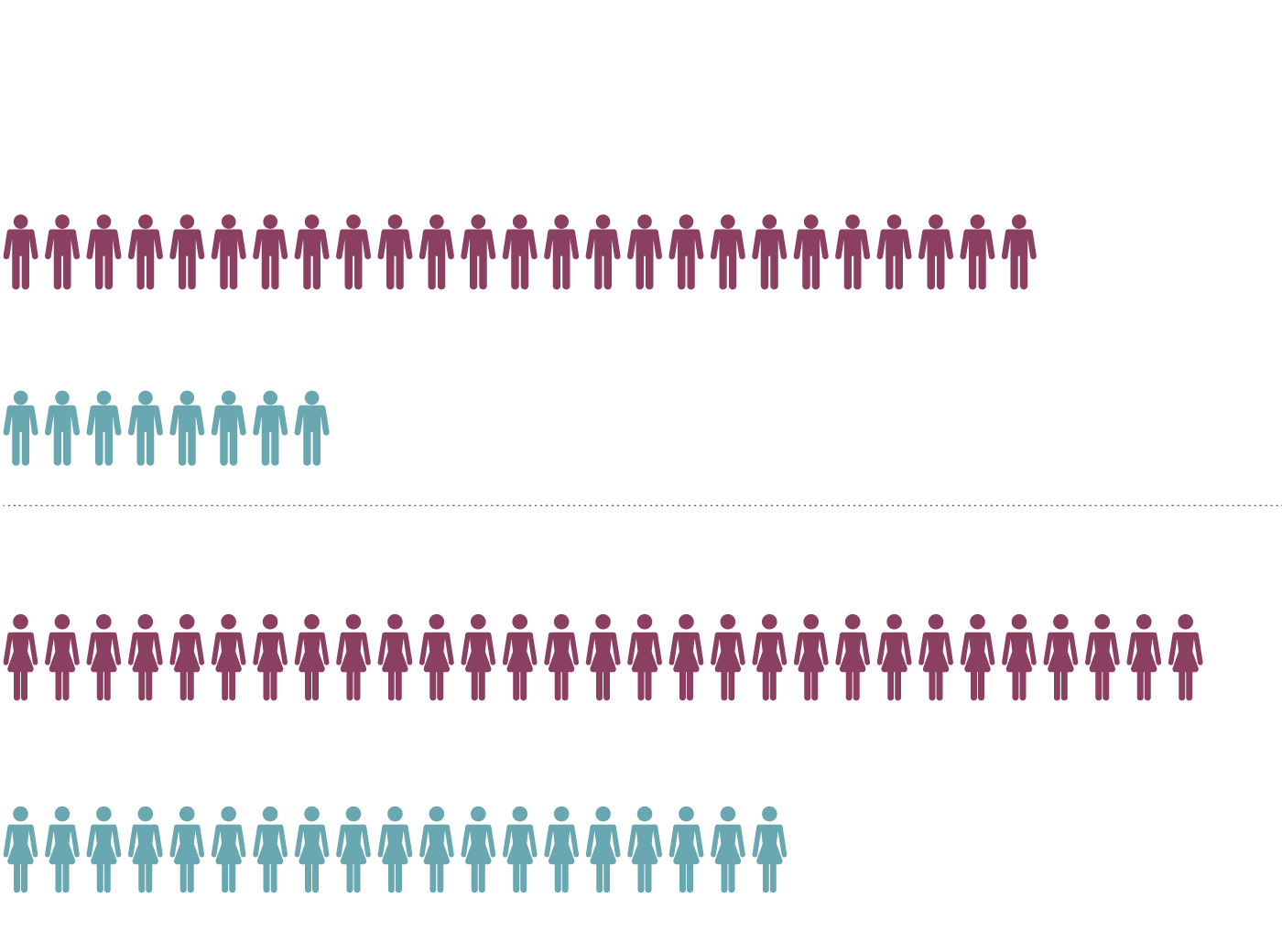

Only a fraction of Canadians between the ages of 25 and 64 who live with severe or very severe disabilities benefitted from the federal Disability Tax Credit (DTC) in 2017, the latest available data show.

Canadians aged 25-64 with severe or very severe disabilities (2016 data)

1,468,320

Canadians aged 25-64 who successfully claimed the DTC (tax year 2017)

369,910

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GLOBE AND MAIL CALCULATIONS;

STATISTICS CANADA; CANADA REVENUE AGENCY

Although he was approved for the DTC in 2015, four years later the Canada Revenue Agency once again denied him the credit, which works out to about $2,000 in annual tax breaks for him and his partner and is tied to many ancillary benefits. Canadians usually must reapply for the DTC annually, even if their conditions are considered chronic and have shown no signs of improvement.

Eventually, Mr. Morley took his case to tax court, a process on which he estimates he spent between 10 and 15 hours – broken up in short stretches of 15 minutes to avoid triggering symptoms. In May, in an out-of-court settlement, the agency agreed that he is eligible for the credit. The CRA also said Mr. Morley will maintain eligibility without having to reapply annually, according to documents reviewed by The Globe and Mail.

While Mr. Morley had no issues being approved for Canada Pension Plan Disability (CPPD), a benefit for Canadians with disabilities who have been CPP contributors, some disability advocates say accessing that program can be difficult for those with invisible impairments and tricky diagnoses.

For COVID-19 long-haulers applying for income support, Mr. Morley said, “There’s going to be challenges all around.”

Some Canadians with long COVID have already discovered that. Chantal Renaud, 49, said she was forced to sell her home in Rockland, Ont., and buy a cheaper property in Saint-Pierre-les-Becquets, Que., to free up funds to support herself and her husband, who, like her, has been suffering from debilitating post-COVID symptoms since the spring of 2020.

After spending June and early July 2020 barely able to get out of bed, Ms. Renaud said, she started feeling better. In September of that year, as her short-term disability benefits ran out, she attempted to return to her job as a communications professional for a hospital foundation.

“I went back to work for one day and I was surprised. I was like, ‘Wow it actually went really well,’” she recalled. But when she woke up the next day, the exhaustion had become so overwhelming she found she couldn’t even move her body in bed.

“I was completely crushed,” she said.

Since then, she has learned that her symptoms become worse after physical or mental exertion, something many other long-haulers have described. Concentrating for too long can bring on throat soreness, breathing problems, palpitations and insomnia, in addition to profound fatigue, Ms. Renaud said. Sometimes she can hear a crackling sound coming from her lungs as she breathes, she added.

Two years in, Ms. Renaud, who left her job in fall 2021, has learned to pace herself. Fifteen minutes spent walking or tending to her garden, for example, require prolonged rest afterward, so she can avoid a relapse that could last weeks. After many tests, her family doctor diagnosed her with post-viral syndrome likely linked to COVID-19.

And yet, Ms. Renaud’s long-term disability claim through her former employer’s group benefits plan was rejected. One major issue: neither she nor her husband ever took COVID-19 molecular tests, which were hard to obtain in the early stages of the pandemic.

Not having a positive molecular test result to prove an initial COVID-19 infection is a common challenge for long-haulers filing disability insurance claims, said Nainesh Kotak, of Toronto-based Kotak Personal Injury Law.

Access to molecular tests has been restricted in various parts of the country and to varying degrees throughout the pandemic. When Ontario was responding to the first wave of Omicron infections last winter, for example, the provincial government said publicly funded tests would only be available to people at high risk from the disease. Others showing symptoms were told to assume they had COVID-19 and isolate.

Not having a positive test isn’t “fatal” to a long-term disability claim, Mr. Kotak said. He recently helped a client make a claim without one. But limits on testing have caused issues for long-haulers, he said.

And with or without a positive test, arriving at a long-COVID diagnosis isn’t easy. Some long-haulers were very sick during their initial infections, while others experienced only mild symptoms at first. There is no standard diagnostic test doctors can rely on the way they rely on procedures such as colonoscopies or mammograms. Some patients who exhibit debilitating long-COVID symptoms have shown no anomalies on a multitude of common medical tests.

“Because sometimes all the usual tests are normal, often patients are told that everything is normal – that it is a mental health issue,” said Angela Cheung, a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto who is working on several large studies focused on long COVID.

But researchers using experimental tests and protocols have detected a variety of abnormalities in long-COVID patients, including those with normal diagnostic test results, she noted. Specially developed blood tests, for example, have revealed differences in the activation of T cells – which are part of the immune system – between people who have recovered from COVID-19 and those who continue to have symptoms, Dr. Cheung said.

In London, Ont., researchers at Western University have discovered, using a 7-Tesla MRI scanner, that there are anomalies in the tissue microstructure in the brains of some long-COVID patients. The machine is several times more powerful than conventional MRIs and provides uniquely high-resolution images of the brain, said Robert Bartha, an imaging scientist and professor of medical biophysics at Western.

“We do know that long COVID is real,” Dr. Cheung said.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/IU4VCVK7DBCJPM3BHERQGP7PFI.JPG)

Researchers at Western University have discovered that there are anomalies in the tissue microstructure in the brains of some long-COVID patients.GEOFF ROBINS/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

But the tests researchers are using to study the condition are so far neither widely available nor easy to deploy on a large scale – and there’s no single test that in itself is enough to lead to a diagnosis, she added.

That’s why doctors must rely on a clinical diagnosis for long COVID – an assessment based on a patient’s symptoms, health history and the ruling out of other possible causes.

The trouble, though, is that “there are actually very few physicians now who are even comfortable making that diagnosis in a firm way,” said Gary Bloch, a family physician at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital.

Even a long-COVID diagnosis isn’t a guarantee of success for either insurance claims or government support programs, experts say.

Ms. Torreiter said some patients at Providence Healthcare’s post-COVID clinic in Toronto have had their workplace long-term disability insurance claims rejected despite support letters from the clinic’s staff detailing their conditions and how their symptoms impair their ability to work.

“It’s very company to company,” she said. While some patients have had their claims approved with no issues, others have received rejections based on reasoning that, in some cases, “almost seems to be questioning whether post-COVID condition exists,” Ms. Torreiter said.

In an e-mailed statement, the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association said insurers assess claims for disability benefits “based on whether the person is sick and cannot work and meets the definition of disabled as defined within the plan and that satisfies the contractual waiting period.” A positive diagnostic test result is “not necessarily a requirement for a disability insurance claim,” the association said.

Ms. Renaud is suing her former employer’s insurance company over its rejection of her long-term disability claim. After experiencing a severe relapse when she spent one afternoon applying for a remote job, she resolved to apply for CPPD. It took her about two weeks to get the paperwork done because she couldn’t spend much time at her computer, she said. She has been waiting to hear back since December.

Her husband is receiving regular CPP payments after retiring early following a few unsuccessful attempts to return to work, she said. The couple currently survives on his monthly pension benefit of around $1,300, as well as $1,500 a month from their personal savings, much of which came from selling their Ontario home.

Ms. Renaud said she continues to hope she will eventually be able to receive some disability income before reaching the age at which she will be able to access her own retirement benefits.

For other long-haulers, the only potential source of disability income is the government. In Burnaby, Mr. McGarva, who is 43, said his former part-time job as a radio producer didn’t come with disability insurance. His spouse’s group benefits won’t cover him either, he said.

Mr. McGarva said he became violently sick with COVID-19 in early March 2020. He said the disease made it so hard to breathe he at times feared for his life. A chest X-ray would later show extensive damage to his lungs, he added, and he has since suffered from impairing fatigue. He’s currently living off his wife’s income while he explores federal and provincial government benefits.

But the government safety net has significant holes for Canadians with long COVID, according to Jennifer Robson, a professor of political management at Carleton University.

Employment Insurance sickness benefits are primarily meant for people who are considered likely to be able to return to their jobs after they recover from relatively short-term illnesses or injuries, she said. The benefits provide up to 15 weeks of financial assistance – 55 per cent of eligible earnings up to a maximum of $638 a week – though Ottawa has pledged to extend that to 26 weeks, as of this summer. Still, the program is only for those who have logged a minimum number of work hours, and it often isn’t available to freelancers.

CPPD is at the other end of the spectrum when it comes to attachment to the work force, Ms. Robson noted. The program provides partial income replacement for those who can’t work owing to disabilities that are long-term, lifelong or likely to result in death. But the benefit is only available to those who have reached minimum thresholds for CPP contributions.

The DTC, which is a non-refundable tax credit, doesn’t provide income, but it guarantees qualified recipients access to a host of other resources, including the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP), a registered account for people with disabilities. Each of those accounts is eligible for up to $70,000 in government matching grants and $20,000 in government bonds.

But filing a DTC claim can be complex. An entire consulting business exists for the sole purpose of helping Canadians with disabilities and their families access the credit, Ms. Robson said.

Eligibility isn’t based simply on a diagnosis. Instead, the application form requires health care practitioners to indicate – often in a tick-the-box format – how an applicant’s disability impairs them in daily activities such as eating or getting dressed. For conditions like ME/CFS and long COVID, among others, trying to quantify the severity and duration of patients’ limitations can get particularly tricky, Ms. Robson said.

Canadians with severe disabilities who work part-time

Among those aged 25 to 64, Canadians with severe disabilities are much more likely to be working part-time compared to those without disabilities.

Share of men with severe disabilities working part-time

25%

Share of men without disabilities working part-time

8%

Share of women with severe disabilities working part-time

29%

Share of women without disabilities working part-time

19%

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: STATISTICS CANADA

A 2018 report by researchers at the University of Calgary found that only 40 per cent of working-aged adults with severe disabilities were using the DTC. Since then, the CRA has tweaked the vetting process for the credit, including by introducing a digital application form and hiring people to help taxpayers navigate their claims. Some public policy and disability advocates, though, say the credit needs a radical overhaul to make it more accessible.

Provincial social assistance benefits, another common source of financial help for people with disabilities, often provide incomes far below poverty levels, Ms. Robson noted.

At both the federal and provincial levels, she said, public disability benefits are ill-equipped for a condition like long COVID, whose symptoms can ebb and flow, allowing some sufferers to work part-time.

The Trudeau government retabled legislation at the beginning of June to create a federal disability benefit. A similar, previously introduced bill died when the 2021 federal election was called.

Some advocates and public policy experts say they hope the benefit will plug some of the gaps in the country’s system of public supports, and lift working-age Canadians with disabilities out of poverty.

But the impact of a new federal benefit will depend on how it is designed, Ms. Robson said. One concern is that eligibility for the payments could be linked to the DTC, which, she said, would be “a recipe for disaster” without significant reforms to the tax credit.

In the meantime, many long-haulers continue to fend for themselves.

Ms. Renaud said the lack of either insurance or government income support is hard to bear, both financially and psychologically.

“I’m really angry about the whole thing because I’ve contributed to this country for over 33 years, and to be treated like this now, because I got sick from an illness that continues to kill and disable millions around the world, is really frustrating.”